Jean Dubuffet’s Monumental Vision at Galerie Lelong Paris

The “Papa of Art Brut” turned boring phone calls into his famous hourloupe style! Galerie Lelong builds Jean Dubuffet legendary bench and kites that were too wild for his own space. These works are now the stars of a rare collaboration between Galerie Lelong, Fondation Dubuffet, and Pace Gallery. This spring, the art brut pioneer takes center stage in both Paris and New York.

—

The current exhibition at Galerie Lelong Paris brings Jean Dubuffet’s sculptural works to monumental life through a remarkable collaboration with Fondation Dubuffet and Pace Gallery. What makes this show particularly significant is its focus on realized versions of works that existed primarily as concepts and maquettes during the artist’s lifetime.

Central to the exhibition are the full-scale realizations of Dubuffet’s “Banc-salon” (bench-salon) and “Cerfs-volants” (kites) sculptures. Originally conceived as small models in the late 1960s, these works have now been constructed at their intended scale, following the artist’s detailed specifications with meticulous precision. The transformation from miniature to monument reveals dimensions of Dubuffet’s vision that remained largely theoretical until now.

The “Banc-salon” carries a particularly intriguing history. Dubuffet initially designed this sculptural furniture piece for his ambitious “Cabinet logologique” – an immersive room-sized installation he described as his “chamber of philosophical exercise.” However, practicality eventually trumped concept when the artist realized the bench would consume too much valuable floor space within the installation, leading him to abandon its inclusion. This tension between artistic ambition and spatial constraints offers insight into the pragmatic challenges that shape even the most visionary creative practices.

Similarly, the “Cerfs-volants” sculptures traveled a winding path from conception to realization. First designed for another project altogether, these works were later considered for potential incorporation into the “Cabinet logologique” before being set aside again. These sculptures, with their distinctive cellular patterning, exemplify what might be called Dubuffet’s artistic orphans – works conceived with purpose but left unrealized due to shifting priorities and practical limitations.

The exhibition thoughtfully incorporates original maquettes of “Chiens de guet” (watchdogs) from 1969, providing visitors with a window into Dubuffet’s creative process. These preliminary models demonstrate how the artist approached the technical challenge of wrapping his characteristic linear patterns around three-dimensional forms. The transition from flat surface to volumetric presence reveals the spatial thinking that underpinned Dubuffet’s seemingly spontaneous mark-making.

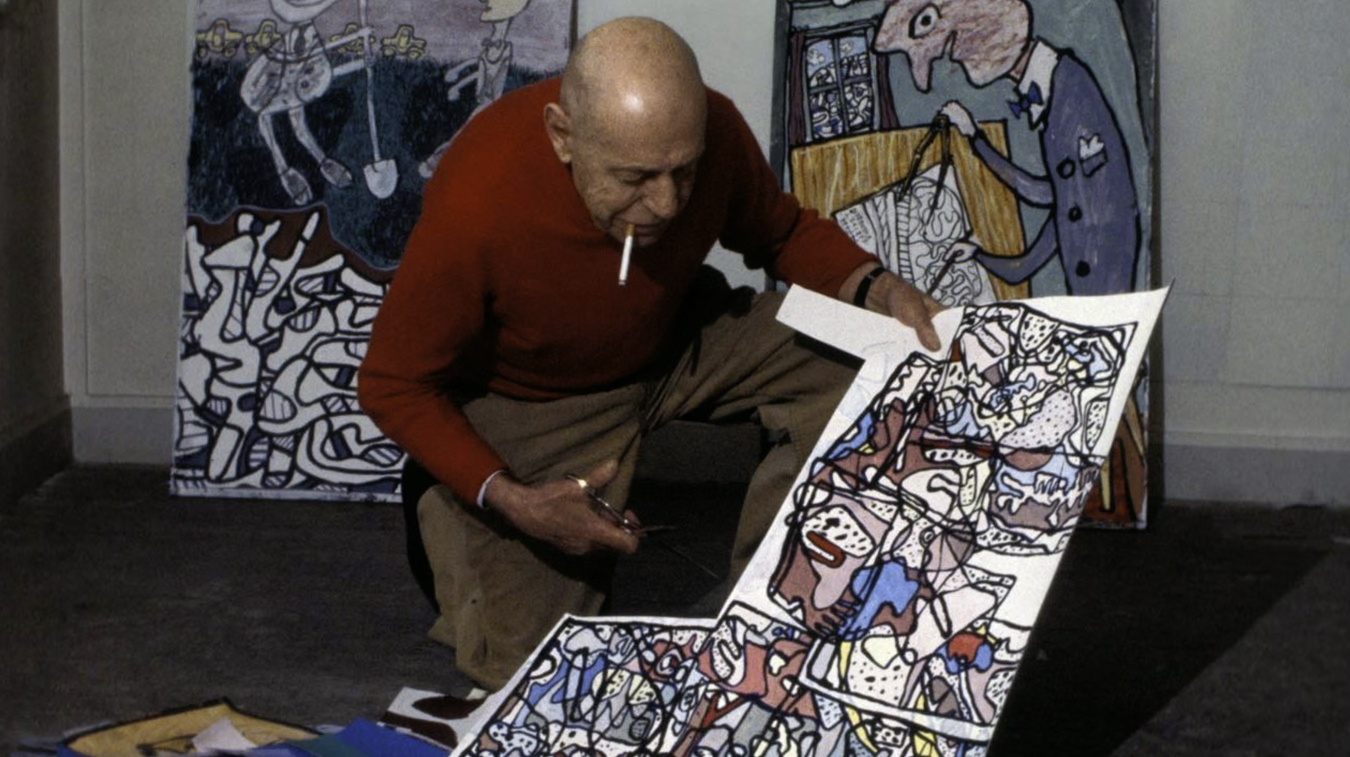

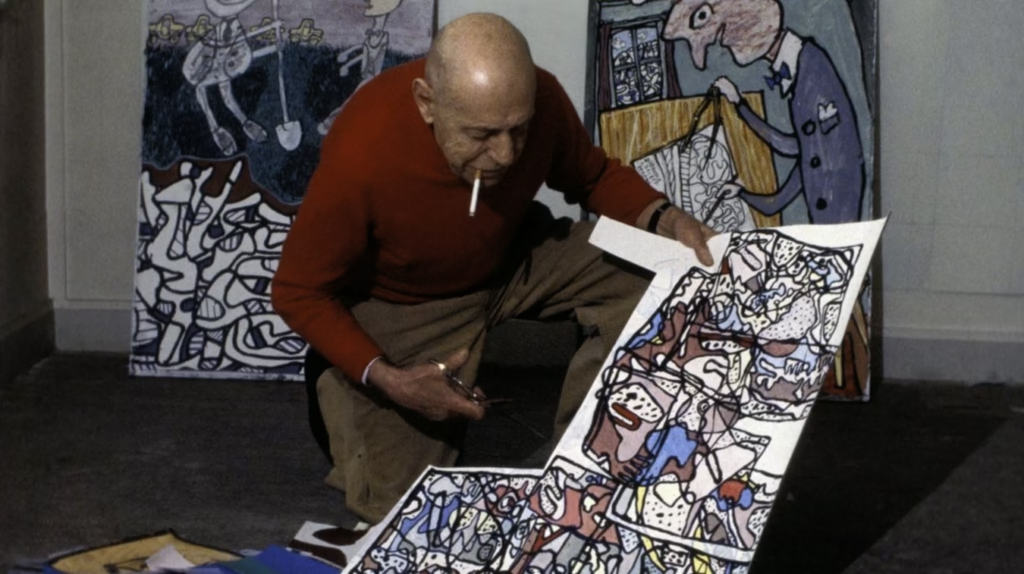

What unifies these works is Dubuffet’s distinctive “Hourloupe” style – the interconnected cells of red, white, and blue that became his visual signature from 1962 onward. The origin story of this aesthetic approach provides a compelling reminder of creativity’s unpredictable sources. These instantly recognizable patterns emerged from doodles Dubuffet made while engaged in telephone conversations – casual markings that evolved into one of the most identifiable artistic vocabularies of the 20th century.

This historical detail illuminates the exhibition’s broader conceptual framework: the journey from small beginnings to monumental outcomes. The telephone doodles that launched an artistic style now find their ultimate expression in these fully realized sculptural works, completing a creative cycle that spans from the intimate to the architectural.

The Galerie Lelong exhibition operates in dialogue with two concurrent Dubuffet presentations: “Dubuffet Monumental” at Fondation Dubuffet in Paris (running through July 11) and “The Hourloupe Cycle” at Pace in New York (through April 26). Together, these exhibitions offer an unusually comprehensive view of the artist’s approach to dimensional work across both proposed and completed projects.

What distinguishes this particular showing is its focus on realization rather than retrospection. Rather than simply documenting what Dubuffet created during his lifetime, the exhibition actualizes what might have been – transforming hypothetical works into tangible experiences. This approach raises fascinating questions about posthumous artistic production and the realization of unrealized concepts.

For visitors familiar only with Dubuffet’s better-known two-dimensional works, the exhibition reveals the spatial thinking that informed even his flat surfaces. The cellular patterns that might appear purely decorative in paintings take on structural and architectural qualities when wrapped around three-dimensional forms. This transformation highlights Dubuffet’s understanding of pattern as both visual and structural language.

In its thoughtful presentation of both original models and newly realized works, the exhibition navigates the delicate balance between historical fidelity and contemporary relevance. These sculptures – conceived half a century ago but only now fully realized – collapse time in a way that makes Dubuffet’s vision feel surprisingly current. The show serves as a potent reminder that significant artistic ideas maintain their potency across decades, waiting for the right moment to achieve their full expression.

Address:

Galerie Lelong

13 rue de Téhéran

75008 Paris