“The Art of Encounter” at Mennour Gallery

I walked in expecting the usual gallery setup. Got hit with Kapoor’s mirror that flips reality upside down, right next to Ugo Rondinone’s pink-grey nun standing like it’s been there for centuries. Weird combo that actually works. The real surprise? Fila’s wrapping a vine trunk in 200-year-old linen next to Kwade petrified tree. Both artists basically saying ´time is weird’ in completely different languages.

—

The current exhibition at Mennour Gallery, “The Art of Encounter,” brings together an eclectic group of artists whose works create unexpected conversations about time, nature, and materiality. This thoughtfully curated show rewards visitors with surprising contrasts that challenge conventional gallery expectations.

Upon entering, Anish Kapoor’s concave mirror (2018) immediately disrupts spatial perception, inverting the gallery space and destabilizing the viewer’s relationship to their surroundings. Nearby stands Ugo Rondinone’s pink-grey basalt “nun” (2024), its stoic presence suggesting both ancient permanence and contemporary minimalism. This initial pairing establishes the exhibition’s pattern of creating productive tension between works that might initially seem conflicting.

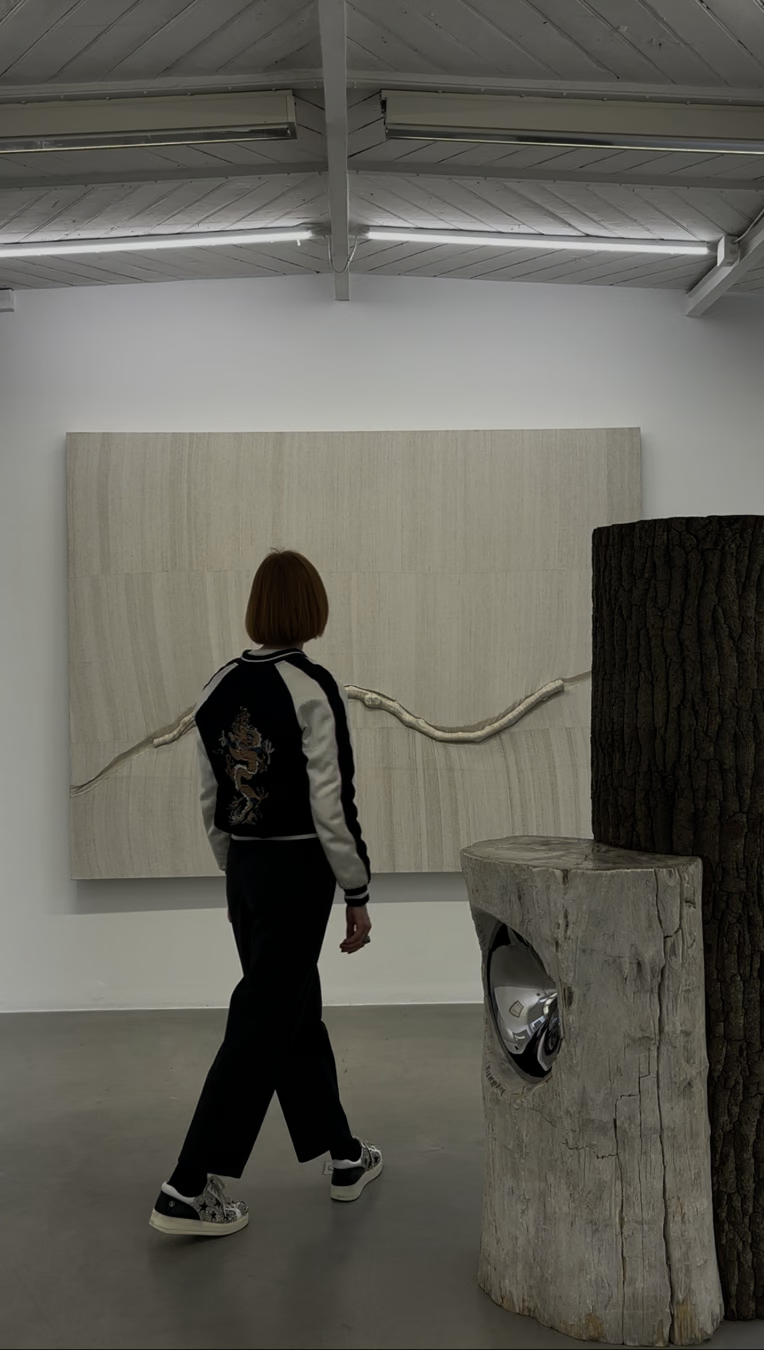

The exhibition’s most compelling dialogue occurs between Sidival Fila’s vine trunk wrapped in 19th century linen and Alicja Kwade’s petrified tree (“Äußere Beschaffenheit,” 2024). Both artists engage with temporality through natural materials, even though their methods are quite different. Fila’s intervention—applying centuries-old fabric to organic matter—creates a meeting point between cultural history and natural processes. Kwade, meanwhile, presents a tree transformed by geological time, its wooden structure converted to stone through natural processes. Together, these works offer complementary meditations on time’s passage and human interventions in natural cycles.

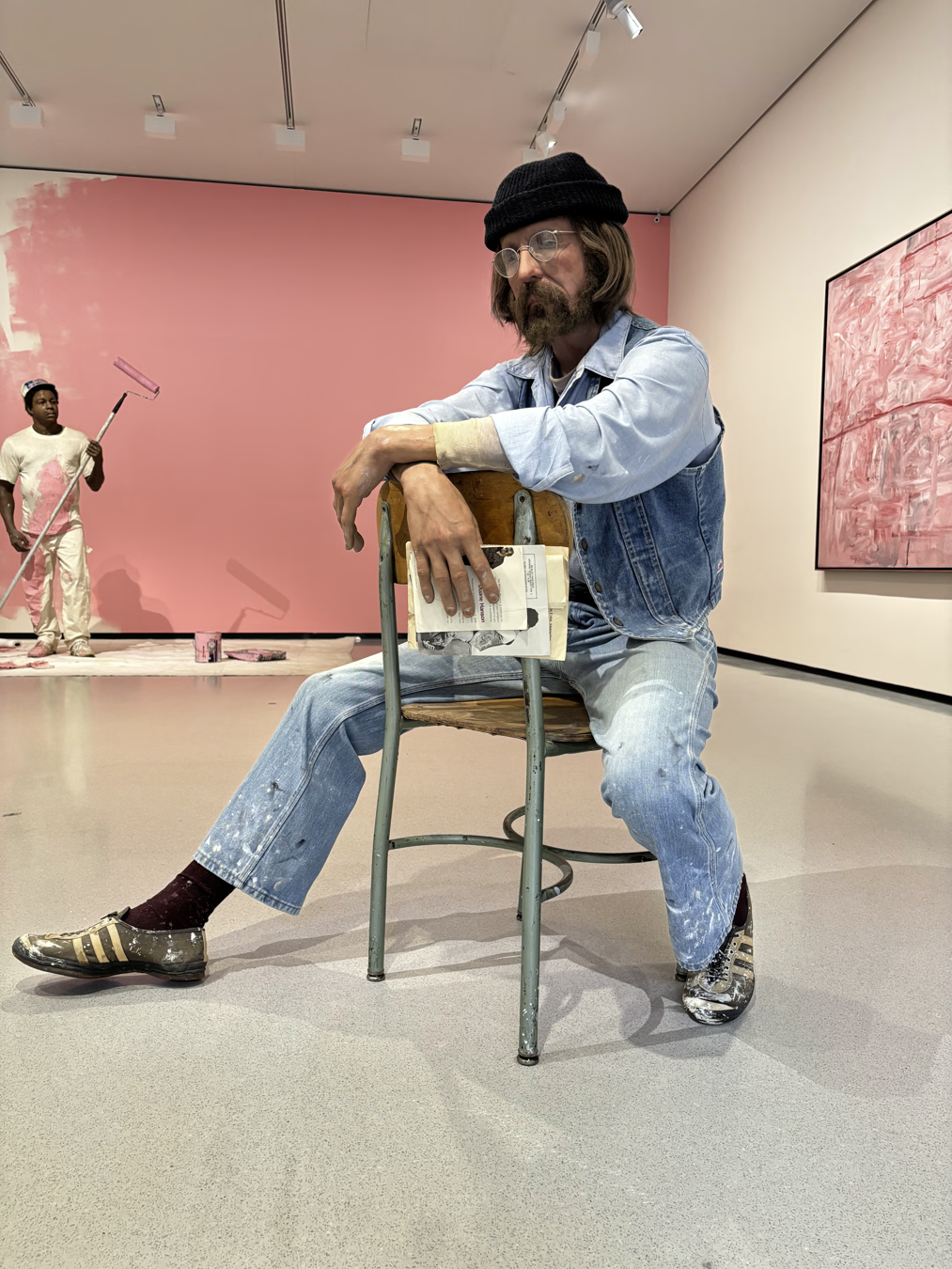

François Morellet’s “Geometree” (1983) provides another perspective on the nature-culture relationship. The work imposes mathematical precision onto organic form, suggesting both harmony and discord between human systems and natural growth patterns. This conceptual territory finds a counterpoint in Camille Henrot’s “Prima Ballerina” (2023), which captures an orange peel’s spiral form. Henrot’s work reveals the inherent geometry in organic structures, positioning nature as the original mathematician. The contrast between these approaches—Morellet’s imposition versus Henrot’s revelation—creates a subtle but provocative dialogue about human attempts to understand and categorize the natural world.

Among these conceptually driven works, Judit Reigl’s “Deroulement” (1978) offers a more purely painterly experience. This understated canvas captures fluid movement with remarkable economy, demonstrating how abstraction can convey sensation without explicit representation. While less immediately attention-grabbing than Kapoor’s mirror or Rondinone’s sculpture, Reigl’s painting rewards sustained viewing with its nuanced exploration of movement and materiality.

The exhibition’s strength lies in these thoughtful pairings and the space given for works to resonate with each other. Rather than overwhelming visitors with excessive pieces or explanatory text, “The Art of Encounter” creates room for genuine discovery. The curatorial approach trusts viewers to find connections between works without prescribing specific interpretations.

For those weary of pretentious gallery experiences, this exhibition strikes a refreshing balance. The works are conceptually rich without being inaccessible, and the presentation avoids both oversimplification and needless obfuscation. The result is an exhibition that engages both emotionally and intellectually without resorting to art world clichés.

Address:

Mennour Gallery

47 Rue Saint-André-des-Arts

75006 Paris