When women’s stories are on display, who should tell them?

At Perrotin Paris, Pharrell Williams curates “FEMMES” – an exhibition about women’s narratives that awkwardly includes 10 men among its 40 artists. This contradiction frames the entire show, revealing art world power dynamics that persist even in spaces supposedly dedicated to female voices. Still, the art cuts through: Muriu’s subjects hide in vibrant fabrics, Camara’s terracotta sculptures radiate primal power, and Choumali’s embroidered photographs transform passive documentation into active expression.

—

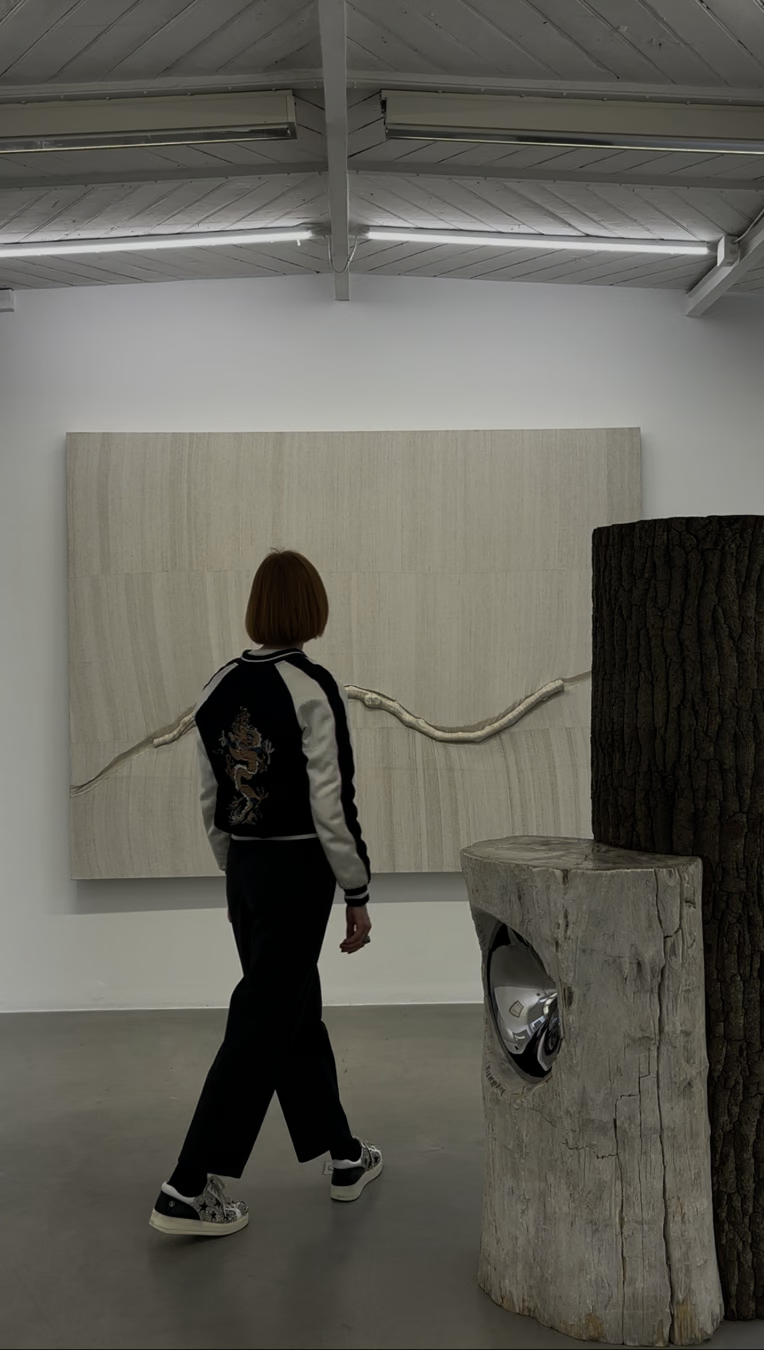

The celebrated Perrotin gallery in Paris currently hosts “FEMMES,” an exhibition curated by Pharrell Williams—better known as Louis Vuitton’s Men’s Creative Director. The show presents itself as a platform for women’s narratives in contemporary art, yet the curatorial framework raises questions that cannot be ignored.

From the outset, a fundamental tension emerges: an exhibition titled “FEMMES” (Women) features 10 men among its 40 artists. While female artists constitute the majority, this gender disparity within a show explicitly focused on women’s stories creates an immediate conceptual dissonance. This curatorial choice reflects broader patterns within the art world, where even spaces dedicated to women’s voices often cannot fully escape male presence and authority.

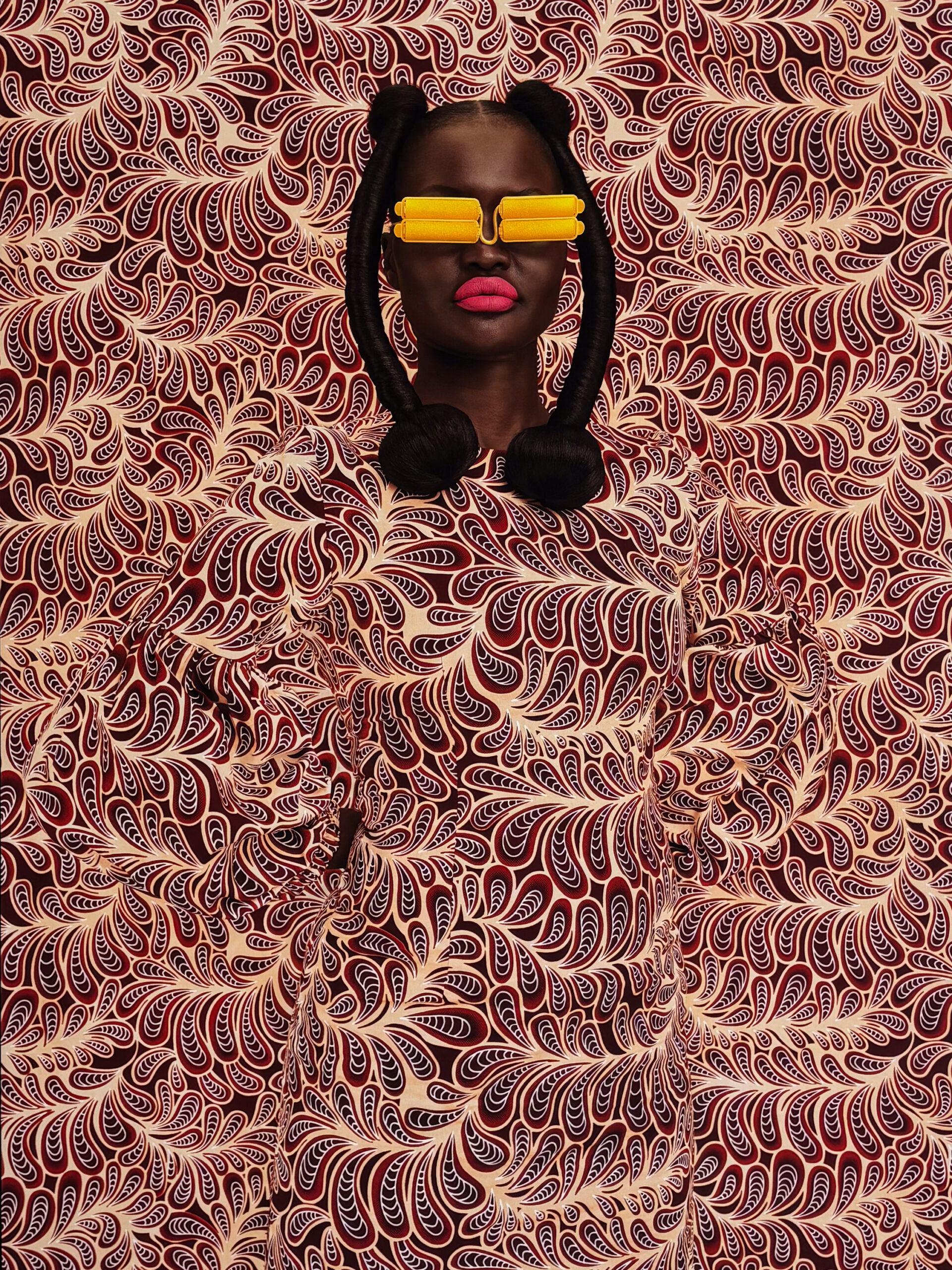

Despite these conceptual contradictions, the exhibition delivers several powerful artistic encounters. Thandiwe Muriu’s “A Constellation of Power” employs vibrant, eye-catching fabrics as backgrounds that simultaneously camouflage and highlight her female subjects. The visual tension between visibility and concealment creates a compelling metaphor for women’s experiences in society—hidden in plain sight yet commanding attention once perceived.

Seyni Awa Camara’s terracotta sculptures stand as another highlight. These figures possess an undeniable presence, their earthy materiality and unrefined surfaces conveying a sense of primal power. Camara’s work draws from Senegalese traditions while speaking to universal themes of feminine strength and embodiment. The sculptures’ raw, tactile quality offers a welcome counterpoint to more polished contemporary art practices.

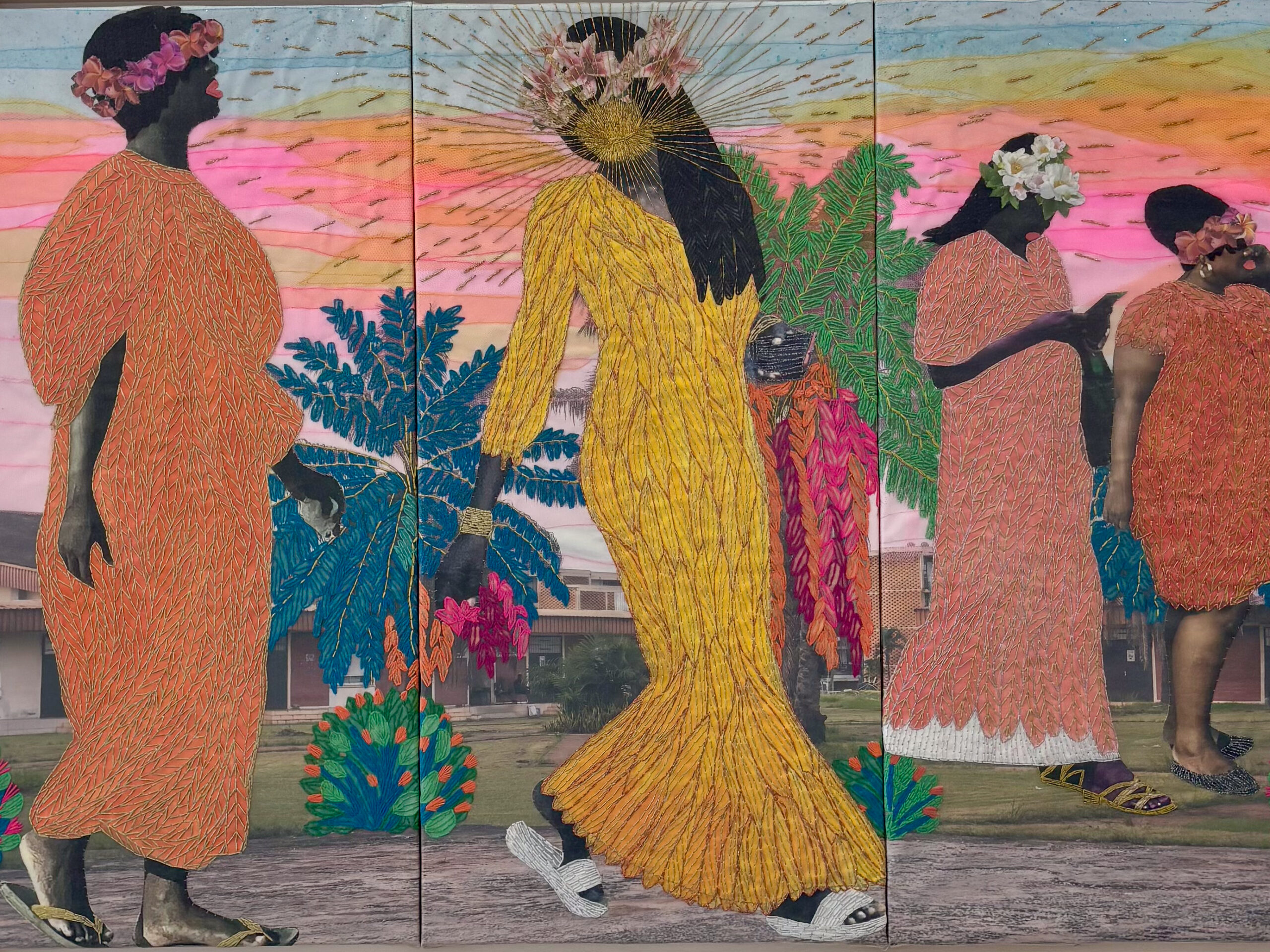

Another artist whose work stands out is Joana Choumali. Her embroidered photographs merge documentation with artistic intervention. By stitching colorful threads across photographic images, Choumali creates multilayered narratives that extend beyond visual representation alone. These works operate at the intersection of photography, textile art, and storytelling, offering nuanced perspectives that resist simple interpretation. The added dimension of embroidery transforms passive documentation into active expression.

What complicates this exhibition is not the quality of the artworks themselves, but the framework through which they reach their audience. Williams, as curator, inevitably filters these women’s stories through his own perspective and taste. His selection process—which artists to include, which to exclude—carries significant influence in determining which women’s voices are amplified and which remain unheard.

The exhibition’s prominence stems largely from Williams’ celebrity status and fashion industry connections rather than from the artists’ work alone. This reality raises uncomfortable questions about visibility and opportunity in the art world. Would these same artists have received this platform without a male celebrity curator? Does the amplification of their work through Williams’ curatorial lens justify the implicit power dynamics at play?

These questions reflect broader systemic issues rather than specific criticisms of Williams or the exhibition itself. The art world continues to struggle with gender parity, with men historically dominating roles of influence as gallery owners, curators, critics, and collectors. Even well-intentioned efforts to elevate women’s voices often operate within these established power structures.

“FEMMES” thus exists at an uneasy intersection. It provides valuable visibility for female artists while simultaneously reinforcing the pattern of male gatekeeping that has long characterized the art world. The exhibition succeeds in presenting compelling artwork but fails to resolve the contradiction embedded in its premise.

For visitors, this tension need not diminish the experience of engaging with the art. Muriu’s vibrant portraits, Camara’s powerful sculptures, and Choumali’s embroidered photographs remain potent regardless of curatorial context. These works speak with distinctive voices that transcend the exhibition’s conceptual limitations.

However, critical viewers might question what a truly radical platform for women’s artistic voices would look like. Perhaps such a platform would feature exclusively female artists. Perhaps it would extend beyond representation to include female curators, writers, and facilitators throughout the exhibition process. Perhaps it would consciously create structures that challenge rather than accommodate existing power dynamics.

As “FEMMES” demonstrates, simply including women’s work within traditional exhibition frameworks may not be sufficient to fundamentally shift the art world’s gender politics. The question remains: when women’s stories are displayed in prestigious galleries, who should control how they’re told, contextualized, and received? The answer seems increasingly clear, even as the art world’s practices lag behind this understanding.

In the meantime, visitors to Perrotin can appreciate the significant talents on display while acknowledging the complicated dynamics that brought them together. The exhibition succeeds as a showcase for compelling contemporary art while simultaneously serving as a case study in the challenges of genuine gender equity in the art world.

Address:

Perrotin Gallery

76 rue de Turenne

75003 Paris